Ancient Greeks & the Foreskin

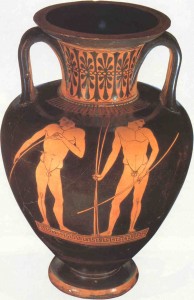

The ancient Greeks were a culture which promoted the possession of a generous foreskin as a significantly important part of their way of life. They were also gainst the practice of circumcision which they viewed as abhorent. Many pieces of ancient Greek artwork depict scenes of naked men endowed with quite lengthy foreskins. More importantly they practiced the cultivation of the prepuce and the longer the foreskin the more desired it seemed to be whilst a mega [Greek: mega = large] prepuce or very large foreskin was the epitome of a desirable penis. As previously mentioned the term for the generous abundance of foreskin at the end of the penis is called the acroposthion. Maybe it is the acroposthion then, in all its unashamed obviousness is what’s seen to be the undesirable element by those who advocate universal circumcision, because it is precisely therein this protrusion that lays the source of blissful and intense pleasurable sensations.

The ancient Greeks were a culture which promoted the possession of a generous foreskin as a significantly important part of their way of life. They were also gainst the practice of circumcision which they viewed as abhorent. Many pieces of ancient Greek artwork depict scenes of naked men endowed with quite lengthy foreskins. More importantly they practiced the cultivation of the prepuce and the longer the foreskin the more desired it seemed to be whilst a mega [Greek: mega = large] prepuce or very large foreskin was the epitome of a desirable penis. As previously mentioned the term for the generous abundance of foreskin at the end of the penis is called the acroposthion. Maybe it is the acroposthion then, in all its unashamed obviousness is what’s seen to be the undesirable element by those who advocate universal circumcision, because it is precisely therein this protrusion that lays the source of blissful and intense pleasurable sensations.

In his publication for ‘The Bulletin of the history of medicine’ entitled ‘The Ideal Prepuce in Ancient Greece’, Frederick. M Hodges documents the preputial aesthetics of the Ancient Greeks, who valued and prized the prepuce on its own merits while simultaneously associating it with other aspects of male beauty. They valued the longer, tapered foreskin as a reflection of a deeper ethos involving cultural identity, morality, propriety, virtue, beauty and health. They also characterized a penis with a short or inadequate foreskin as deficient or defective, especially one that had been surgically removed under their disease concept of lipodermos [Greek = lacking skin].

As would be expected in a culture that valued the prepuce, the Greek language reflected this esteem through precise terminology. The Greeks understood the prepuce to be composed of two distinct structures: the posthe and the ‘akroposthion’. Posthe designates that part of the prepuce that covers the glans penis, but Greek writers occasionally used this word in a general sense to designate the entire prepuce or, by extension, the entire penis. ‘Akroposthion’ designates the tapered, tubular, visually defining portion of the prepuce that extends beyond the glans and terminates at the preputial orifice. When speaking of the iconographic representation of the long prepuce, we are really speaking of the long ‘akroposthion’ for the posthe can never be larger than the unchanging surface area of the underlying glans penis.

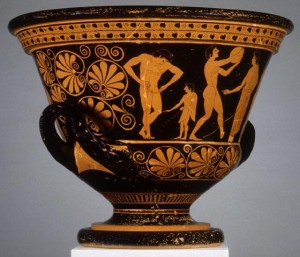

The association between the longer prepuce and respectability was so strongly felt that Greeks took steps to prevent unwanted exposure of the glans. In this regard, the consistent artistic portrayal of the adult penis with a generously proportioned ‘akroposthion’ may well represent an anatomical ideal peculiar to Greeks, but, in some cases, it could accurately represent a penis whose ‘akroposthion’ has been elongated, either deliberately or accidentally through the continuous, long term application of traction. Such traction seems to have been enabled from the use of the kynodesme (literally a “dog leash”), a thin leather thong wound around the ‘akroposthion’ that pulled the penis upward and tied around the waist in a bow, or secured by some other means.

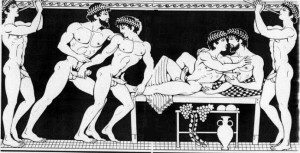

Preventing unwanted exposure of the glans was a sign of the modesty and decency expected in particular of the older participants in the symposium and the unseemly externalization of the glans in public, that a deficient or loose lipped prepuce was unable to prevent was seen as a disgrace and was the main reason for wearing a kynodesme. The kynodesme, then is a means by which any male so affected can maintain his dignity when in the nude. For those who continuously wore the kynodesme, the resulting traction on the ‘akroposthion’ would have the benefit of permanently elongating it. It is conceivable, then, that the lengthening of the prepuce could have been the primary object, at least in some cases as aesthetics would be improved, and morals preserved.

The intensity with which the Greeks esteemed the prepuce was equalled by the intensity with which they deplored its ablation as practiced in certain communities scattered throughout the south eastern fringes of the known world. The Greeks were highly sceptical about any of the religious rationales used by certain foreigners in an attempt to justify their blood rites of penile reduction through the practice of genital cutting of various degrees from circumcision to more severe penile mutilations such as amputating the glans to the even more horrifying amputation of the entire penis. They viewed the circumcised penis (and, therefore, the exposed glans) as primitive, barbaric, backward, superstitious, and oppressive.